Comparison and Controversy

A Cut Above Hifi+Back to the Good Old Bad Old Days: Johanna Martzy LP Reissues

By Roy Gregory, June 11 2014

The world of 180-gram reissues seemed to have settled down -- at least I thought it had. I look back fondly on Chesky’s early efforts: repressings of sought-after classical titles from the RCA and Reader’s Digest back catalogues, a fair price asked for a recording that you probably couldn’t otherwise find. They were populist, high profile and well received -- and therein lies the clue. The elevated reputation enjoyed by those ten or so titles rested on their constant referencing in Harry Pearson’s reviews, their presence on his Super Disc list. Audiophiles, eager to hear the sonic marvels so eloquently described, rushed to secure their own copies of the fabled records, driving up secondhand prices to frankly ludicrous levels -- thus opening the door to reasonably priced reissues conducted with appropriate care and consideration.

The world of 180-gram reissues seemed to have settled down -- at least I thought it had. I look back fondly on Chesky’s early efforts: repressings of sought-after classical titles from the RCA and Reader’s Digest back catalogues, a fair price asked for a recording that you probably couldn’t otherwise find. They were populist, high profile and well received -- and therein lies the clue. The elevated reputation enjoyed by those ten or so titles rested on their constant referencing in Harry Pearson’s reviews, their presence on his Super Disc list. Audiophiles, eager to hear the sonic marvels so eloquently described, rushed to secure their own copies of the fabled records, driving up secondhand prices to frankly ludicrous levels -- thus opening the door to reasonably priced reissues conducted with appropriate care and consideration.The problem was that the Super Disc list was quickly identified as a road map to get rich quick. Anything on the list was bound to sell -- and sell in big numbers. Charge a premium price and the profits would come rolling in -- and they did. But then people started to get even greedier. Having run through the RCA titles on Harry’s list, they started churning out anything with a Living Stereo banner on the sleeve. Then they started in on special editions: early stampers, 200-gram vinyl, no groove guard, 45rpm cuts, 45rpm single-sided cuts -- turning a single album into a four-disc set, at four times the price! With such wanton excess it’s hard to fix on a single low point, but limited to six titles from the Mercury back catalogue, Classic Records' choosing to include (and subsequently offer 45rpm versions of) both Balalaika Favorites and the Fennell Hi-Fi A La Espagnola has to come close.

Since those dark days, vinyl’s own "greed is good" era, things have improved significantly. Even the notoriously forgiving audiophile audience began to tire of yet another high-priced sonic spectacular that wasn’t. These days 180-gram pressings tend to be far more repertoire-led, and quality and consistency have improved significantly. The likes of Speakers Corner, Analogue Productions, Mobile Fidelity and others are reliable sources of beautifully pressed, pristine editions of material it is otherwise hard to find and seriously expensive to buy. Prices have settled out to around $30 a disc and even current 45rpm editions have started to deliver on their sonic promise. You still get the odd lemon, or record that you look at and find yourself asking, "Why?" but then that’s life, and one man’s lemon is another’s lemonade.

Which brings me to the subject of the Electric Recording Co. (ERC), another of the burgeoning number of "specialist" reissue houses concentrating on re-creating "iconic ‘Holy Grail’ recordings" using an all-tube cutting chain and vintage equipment, including a mono cutter for mono discs. Their site talks -- at length -- about the glorious treasure trove of now sadly unavailable classical recordings made in the ‘50s and early ‘60s, by artists such as Martzy, Kogan, Lefébure and Starker and how these rare early recordings, when they do come up for sale, command prices they describe as "jaw-dropping." So far so good -- if a little florid. However, they then go on to say, ". . .all of which underscores what a major coup the Electric Recording Co. have pulled off in licensing key catalogue titles, almost exclusively from the aforementioned ‘golden age.’" Leaving aside the whole concept of anything being "almost exclusive," their first three issues -- collectively the Martzy EMI recordings of the Bach Sonatas and Partitas -- are already available from the established Coup d’Archet label. Okay, there is an issue here -- the Coup d’Archet edition is part of a ten-record box set that will cost you the not inconsiderable sum of £300 (around $450) -- so we’re not pricing like with like. But then Coup d’Archet give you the complete Martzy EMI recordings for your £300, in a beautifully presented, fabric covered slipcase. In contrast, ERC price the three-record Sonatas and Partitas "set" individually -- at £300! That’s £300 each, or £900 for the complete set!

ERC make great play of both the rarity of the original discs and the extortionate prices they command secondhand -- although is that reason enough to charge equally extortionate prices for reissues? Perhaps their reasoning is revealed in their choice of the legendary Oubradous Mozart à Paris seven-disc box set from Pathe as their follow-up issue, a set that’s legendary more for its secondhand price than any particular artistic merit. The cost of the ERC issue of this masterpiece? £2495 -- which is around 4000 of your Yankee greenbacks! They also make great claims for the integrity and authenticity of their process, from the record cutting and pressing to the "opulent, hand-crafted jacket artwork" and "painstakingly retyped brass letterpress print procedure."

Now, I’m a sucker for a thing of beauty. It matters to me how things look and how things feel, and, yes, I will (and do) happily pay a premium for "nice" things. But how nice does a record sleeve have to be and how good does that record have to sound -- how much better than the other versions available -- to justify parting with £300 for a single disc? And this is not a purely academic question. As somebody who spends a lot of time (and money) listening to violinists perform -- live and on disc -- and as an acknowledged Martzy fan, I’m not just slap bang in the middle of the ERC’s target audience. I’d happily part with the cash if I was convinced. So, I thought, I owe it to the readers -- a thinly veiled euphemism for "myself" -- to find out just how good the ERC Martzy records really are.

With the Coup d’Archet set already in my collection, what I needed was an example of an ERC pressing and an original to compare it to. An original? Aren’t they incredibly rare and hideously expensive? How could I possibly lay my hands on such a precious artifact? Simple -- ask! The world of truly collectible records is small indeed, and the number of people able or willing to drop four-figure sums on rare discs is even smaller, so if you have connections with the record-selling or specialist record-buying communities, it doesn’t take long to find what you are looking for. Duly equipped with a particularly nice and near-mint copy of the original EMI Columbia 33CX 1287, the middle disc from the set, but crucially featuring the famous Chaconne from Partita No.2, I sat down for some serious comparisons between the original pressing, the Coup d’Archet version and a brand-spanking-new, sealed copy of the ERC pressing -- loaned by the owner of the original, who bought it purely out of interest, once I’d explained why I wanted to borrow his cherished EMI. After all, if you’d dropped a couple of thousand on a three-record set, wouldn’t you want to know how it stacked up against a reissue?

That process isn’t quite as straightforward as it might seem, with significant variables to consider. In the end I used a variety of record players and phono stages, including the Allnic H-5000V to allow the use of an EMI EQ curve for the original pressing, the Connoisseur 4.2PLE, the Aesthetix Janus Signature and the Kondo-KSL SFz transformer/M77 phono combination. I ran my own VPI Classic 4/JMW 12.7 combination, allowing for VTA variation, as well as an SME 20/3 and Kuzma Stabi XL, the latter 'tables with either the Viv Lab Rigid Float 7" tonearm or a Kondo-rewired SME V -- although in both cases it was necessary to adjust VTA between discs. Cartridges included my Clearaudio Goldfinger Statement and Lyra Dorian Mono, as well as a Kondo-KSL IO-M, while listening extended across two venues: my own room and system and also a visit to Definitive Audio in Nottingham, where I was able to use both an Auditorium OBX-RW setup and the mighty (and mightily appropriate) Living Voice Vox Olympian/Vox Elysian system, both driven by Kondo-KSL Gaku-Oh amplification. As you can see, this wasn’t a task I undertook lightly, and while repeatedly listening to Martzy play the Bach Partita No.2 is hardly a chore, I wanted to be certain that any conclusions were reliable and repeatable, rather than system-dependent.

Let’s start with that original disc. The first four short parts of the Partita No.2 are recognizably Martzy, with her effortless technique and focused power, qualities that push the music to the fore and make her performances so appealing. The fifth part, the Ciaccona or Chaconne, runs to nearly 15 minutes, its range and virtuosity making it popular as a standalone piece. Interestingly, the sonic perspective shifts noticeably between the nicely balanced opening sections and a bigger, closer perspective adopted for the Chaconne -- almost as if EMI deliberately chose to give it the Hollywood treatment. The result is undeniably powerful, but although it is rich of tone with tremendous presence, it is also bandwidth limited, midrange prominent and lacking texture and dynamic discrimination. That doesn’t stop it being an emotionally intense listening experience, although it is much more about the music than the playing or any sense of the original performance. Despite the LP being a year short of 60 years young, played with the mono cartridge, surfaces were incredibly silent and the sound both fresh and dramatic. Smooth and powerful, this was Cadillac sound, complete with chrome and fins.

Moving on to the Coup d’Archet pressing, we have a very different animal, both technically and sonically. Given the length of Partita No.2 and even though the dynamic demands of solo violin might not seem as demanding as an orchestral piece, Glenn Armstrong has chosen to spread the cut across two sides, giving the Chaconne a side to itself on an "extra" single-sided disc. It was also cut at Abbey Road using modern solid-state electronics and a stereo cutting head. The results are quite different to the EMI original and in their own way especially impressive. Lacking the sumptuous, rounded but rather overblown balance of the EMI, the Coup d’Archet Chaconne, although it still registers the perspective shift of the original, sets the instrument further back in the soundstage, focuses it far more tightly in space and offers greater bandwidth and a far greater sense of the surrounding acoustic. Yes -- I know it’s mono, but mono does depth and it also does reflected energy, so if the system/recording reaches high and low enough you will hear the room in the recording, even if its dimensions aren’t defined. More importantly, there is far more instrumental texture and dynamic resolution. Martzy’s characteristic technique is more obvious -- and significantly more impressive -- the dynamic steps in her playing, her phrasing and the phenomenal range she brings to the piece all the more remarkable. This is much more like sitting listening to a great performer, playing at the top of her game. Instrumental character and complexity, attack and energy, are beautifully clear, the musical flow and those abrupt, almost angular changes of direction and intensity vividly convincing.

Remarkably, the Coup d’Archet cut seems to have lifted significantly more detail off the tape, digging far below the smoothed-off, polished surface of the original, revealing playing of greater agility and control, a musical performance of greater insight and depth.

Which brings us to the ERC disc, product of an all-tube cutting chain and the much-trumpeted vintage mono cutting head. On a purely practical note, the choice of the latter strikes me as frankly obtuse. As anybody who has tried to play an original ‘50s mono disc with a modern stereo cartridge will attest, it doesn’t work. Oh, you get the music, but you get a torrent of groove-bottom rumble and seriously intrusive surface noise too. In fact, the ERC disc was unlistenable with anything other than the mono cartridge. In this respect it was far worse than the original EMI pressing, which whilst it was noisier with the stereo pickups, was still perfectly listenable.

Likewise the sleeve, which is nicely put together but nothing special; I might be more sensitive to print quality than the average record buyer (an occupational hazard), but the quality here is sadly lacking. Placed next to the original -- and making allowances for the fact that they can’t use the Columbia logo -- the weighting of the text is too light, the edge definition poor, and given that this is supposed to be a facsimile copy, why is the Martzy photo on the back incorrect? Both the images on the rear and the velvet "rope" on the front are heavily pixelated and poorly executed, and overall, as far as I am concerned, the presentation doesn’t match the standards described on the ERC website.

Even so, I could forgive the hair-shirt insistence on the mono cutter head (and overlook the cover) if the sonic and musical results justified it. They don’t. In comparison to the other two records the ERC pressing came in a very poor third. The sound was distant, veiled, sadly lacking in dynamic range and strangely disjointed and inarticulate. I guess the one thing in its favor was that it certainly sounded "old" -- but that’s in marked contrast to the presence and power of the original or the vivid agility and textures of the Coup d’Archet. The Chaconne was particularly dire, the rest of the 2nd Partita sounding markedly better, but still not close to either of the alternatives. I could go further, but frankly it would just be unnecessarily cruel. When I first heard the ERC disc I was shocked and nonplussed by the difference between it and the other two versions. The more I listened, across different record players and different systems, the more its dull, congealed and strangely lumpen character intruded on the music, so much so that I took the time and trouble to confirm my findings with other listeners. To date, I’ve yet to find a single fan. This was no system-matching issue or one-off, no flaw in the replay chain or inappropriate choice of equipment. This is actually what the record sounds like -- which makes the price being asked all the more incredible.

I’ve tried to discuss my experience with ERC, but I’ve received no response. You can’t call them and e-mail inquiries have gone unanswered. All of which leads me to one, inescapable conclusion: buyer beware! It’s impossible (and unwise) to speculate as to motive, and I have to assume that the ERC is sincere in its endeavors, but good intentions don’t guarantee good results, and in this case it seems that a rigid adherence to traditional hardware has done them no favors.

I don’t know how many customers they have -- or how happy those customers are -- but audio journalists who should know better (or who should at least make the effort to check the claims) have been seduced by the "original and best" storyline. I for one don’t buy it -- and I won’t be buying any records from the ERC.

Source: Roy Gregory, Audio Beat

www.theaudiobeat.com/blog/martzy.htm

I write regarding a music feature written by Mark Lehman on pp. 142/43 of your current issue (Issue 236, October 2013) concerning the ‘Electric Record Company’ and its reissues of Bach’s works for solo violin as recorded by Johanna Martzy for EMI Columbia. While I have no interest in ERC’s product, I am always extremely interested in comments made regarding my company, Coup d’Archet, which Mr. Lehman chose to mention. The first rule of journalism is ‘check the facts’. A simple Google search for Coup d’Archet would have revealed to him a most informative Web site, www.coupdarchet.com. Informative enough to show that all my LPs featuring Johanna Martzy, both Radio Recordings and EMI Recordings sets, are available, not ‘out of print’. It also offers audio clips, as well as dates and locations of all the recordings.

I write regarding a music feature written by Mark Lehman on pp. 142/43 of your current issue (Issue 236, October 2013) concerning the ‘Electric Record Company’ and its reissues of Bach’s works for solo violin as recorded by Johanna Martzy for EMI Columbia. While I have no interest in ERC’s product, I am always extremely interested in comments made regarding my company, Coup d’Archet, which Mr. Lehman chose to mention. The first rule of journalism is ‘check the facts’. A simple Google search for Coup d’Archet would have revealed to him a most informative Web site, www.coupdarchet.com. Informative enough to show that all my LPs featuring Johanna Martzy, both Radio Recordings and EMI Recordings sets, are available, not ‘out of print’. It also offers audio clips, as well as dates and locations of all the recordings. Mr. Lehman, evidently impressed by ERC’s records and not having the original Columbias, decided he should compare these ERC reissues with ‘one of the Coup d’Archet reissues’ he just happened to have.

Mr. Lehman, evidently impressed by ERC’s records and not having the original Columbias, decided he should compare these ERC reissues with ‘one of the Coup d’Archet reissues’ he just happened to have.

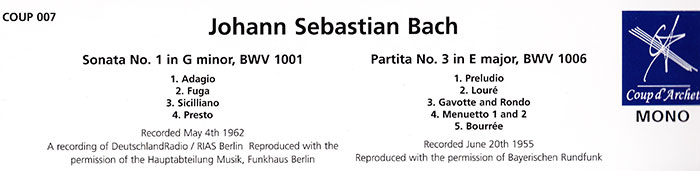

The great pity is that he didn’t actually have one of Coup’s EMI reissues. What he describes is COUP 007, the only record I have produced with the coupling he mentions, BWV 1001 (G Minor Sonata) and BWV 1006 (E Major Partita). The EMI recordings are coupled consecutively, BWV 1001/1002, etc. This fundamental error leads into something rather messy. Had Mr. Lehman an original COUP 007 LP to hand, he could not have failed to notice the prominent Deutschland Radio and Bayerischer Rundfunk logos on each of the labels and on the jacket itself. The recordings on this LP were made live, seven years apart (1962 and 1955 respectively), one in Berlin, the other in Munich.

I quote: ‘On the G Minor Sonata, Coup d’Archet – apparently not happy with the bright, up-close, piercing quality of the mastertapes – has added a touch of reverb, and also some blur, to the sound. On the E Major Partita howver, Coup’s remastering has slathered reverb on so thick that Martzy’s violin is recessed several yards to the rear, out of focus and surrounded by an obscuring veil of synthetic echoes.’ Then our writer notes that ERC’s EMI recording is ‘completely different…highlighting the benefits of eschewing electronic fakery.’ Completely different? You bet. What Mr. Lehman was actually hearing is the sound of the rooms these recordings were made in. He was hearing exactly what is on the tapes. Mr. Lehman has ear enough to notice that the ambient sound is different. It is unfortunate he did not notice that the performances are not the same.

What Mr. Lehman was actually hearing is the sound of the rooms these recordings were made in. He was hearing exactly what is on the tapes. Mr. Lehman has ear enough to notice that the ambient sound is different. It is unfortunate he did not notice that the performances are not the same.

I have never added anything to a recording, not taken anything from one. This is the very foundation of Coup d’Archet’s reputation. One-hundred-percent analogue advance-head mastering directly from the best analogue sources available. Abbey Road mastering engineers, Nick Webb and Sean Magee, have cut the most honest and transparent records I could ever have hoped for over the past 16 years. AR engineers write detailed notes on each and every one of their cuts, just in case the job has to be redone. I can produce their notes for any record I have ever released.

The only reissues Coup d’Archet has ever produced have been the Martzy EMI recordings. Because of my long relationship with Martzy’s legacy and her family, I felt it was necessary to produce a superlative, definitive collection of these beautiful records. The rest of Coup’s catalogue has been licensed from broadcast companies across Europe and are all previously unreleased; not only the recordings, but in most cases, the repertoire. Of the nine discs in my Martzy Radio Recordings collection, all but one are of unreleased repertoire. The obvious exception is COUP 007.

Mr. Lehman has unwittingly damaged Coup d’Archet’s reputation in one of the western world’s more respected audiophile magazines. The least redress I would expect from TAS is that this letter is printed along with a retraction and apology near to the front of the next edition of your magazine.

Glenn Armstrong

Mark Lehman replies: ‘Had Mr. Lehman an original COUP 007 to hand, he could not have failed to notice…’ writes Mr Armstrong. And yet I did fail. As it happens the LP in question belongs to a record-collecting friend not associated with the magazine (who did not buy it from the Coup Web site), and I heard it while visiting him to compare the ERC with the Coup d’Archet reissues. Both of us assumed the Coup d’Archet was one of Martzy’s famous EMI recordings. Neither of us examined the liner notes or disc label, and more important, neither of us had any reason to suspect that Coup d’Archet had issued another recording of Martzy playing the same repertoire (or indeed that such a recording existed). Perhaps I should have thought of this possibility after noting the obvious sonic differences between the Coup LP and that of the Electric Record Company, and checked the liner notes as well as the company’s Web site, but I, in my ignorance, did neither. For this mistake I apologise to Mr. Armstrong, and sympathise with (and indeed share) his dismay. If it is any consolation we at TAS herewith offer to make a comparison between Coup’s EMI reissues and the ERC LPs as soon as we get both discs in hand.

The Absolute Sound, Issue 238, December 2013

Postscript 20 06 2014

Allowing that one of the two chaps removed the record from its rather striking jacket, placed it on a turntable and listened to both sides, I am still incredulous that neither Mr. Lehman nor his friend could have been so disinterested in the content of COUP 007 to fail to notice the info on the jacket verso beneath the titles or the logos and publishing dates on the labels.